Your Next Read: The Book of the New Sun (Review)

A modern masterpiece, worth the time and effort—even if it’s not for you.

Let me start at the conclusion: reading Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun is an incredible, life-changing experience.

As a 55-year-old lifelong reader, I can count on my fingers the number of books that have deeply and irreversibly changed me. New Sun is one of those rare few. I’m only sorry I’m discovering it now, after so many years of reading—but grateful I found it at all.

That being said, a caveat: Wolfe’s novel is not for everyone.

I myself first attempted it fifteen years ago and stopped cold around page thirty. I expect many readers will have a similar struggle. This novel is, well, different. It’s demanding. Disorienting at times, and in many places downright difficult. But if you’re willing to surrender to it, to trust Wolfe’s layered storytelling and let the strangeness wash over you, you may (like me) find yourself changed by the end.

This is a modern masterpiece, and it’s worth your time and effort—even if, in the end, you decide it’s not for you.

New Sun? What New Sun?

The Book of the New Sun was written by Gene Wolfe, a grand master of science fiction. This book is his highpoint.

It’s essentially one long, unified novel, though it was originally published in four volumes between 1980 and 1983: The Shadow of the Torturer, The Claw of the Conciliator, The Sword of the Lictor, and The Citadel of the Autarch.

(Note: There’s also a fifth book—The Urth of the New Sun, published in 1987—which functions as a “coda” or sequel, depending on whom you ask. Want to ignite a heated debate among Wolfe fans? Just assert definitively that the fifth book either is or isn’t an integral part of the series. You’ll stir up a lively ruckus no matter which side you take.)

Summarizing The Book of the New Sun feels a bit like trying to summarize a dream: technically possible, but doomed to miss the point.

In the broadest strokes, the tetralogy follows the journey of Severian, an apprentice in the torturer’s guild (officially, the Order of the Seekers for Truth and Penitence). He is exiled from both his order and city after violating the guild’s code, doing the verboten: showing mercy to a client. He wanders the land—Urth—encountering bizarre figures, monsters, ruins, prophets, and soldiers, gradually rising in stature until he becomes the Autarch, ruler of the Commonwealth.

This is not a spoiler: Severian tells us outright in the first few pages he’ll become the Autarch. You see, this tale is his own account—an autobiography, a memoir, a confession, composed long after the events he describes—and written by a man who claims to possess perfect memory.

That claim is one of many things in the book you’ll come to question.

Welcome to Urth

The first thing to admire about this book—one of the main things that made me fall in love with it—is the world Wolfe has built.

Urth is a strange, decaying landscape. At first, society seems medieval, with swords, castles, guilds, and cloaked travelers. But soon, it dawns on you that something is off. A “flyer” zips across the sky. A beam weapon is fired. We realize that Severian’s home (the Citadel) is actually a ruined spaceship, with metal corridors winding to rooms of half-buried machines. And the moon glows green because once, long ago, it had been terraformed.

This is science fiction masquerading as fantasy—or perhaps fantasy that remembers it was once science fiction. Wolfe plays with our genre expectations in subtle, sophisticated ways. Urth is not a land of dragons and wizards. It’s Earth, unimaginably far in the future—thousands or even millions of years from now. So far ahead that our sun is dying, the planet cooling. Civilization is in decline. History has passed into myth. This is sci-fi’s “dying earth” subgenre perfected: the elegiac, melancholy tone of a civilization long past its zenith, stumbling into twilight.

The result is haunting.

Biotechnology, cloning vats, and interstellar travelers all exist—but all are seen through Severian’s eyes, for whom these things are ordinary, even banal. One of the novel’s great joys is this dissonance: we experience the wonders of the future through the perspective of someone who doesn't understand them as being wonders.

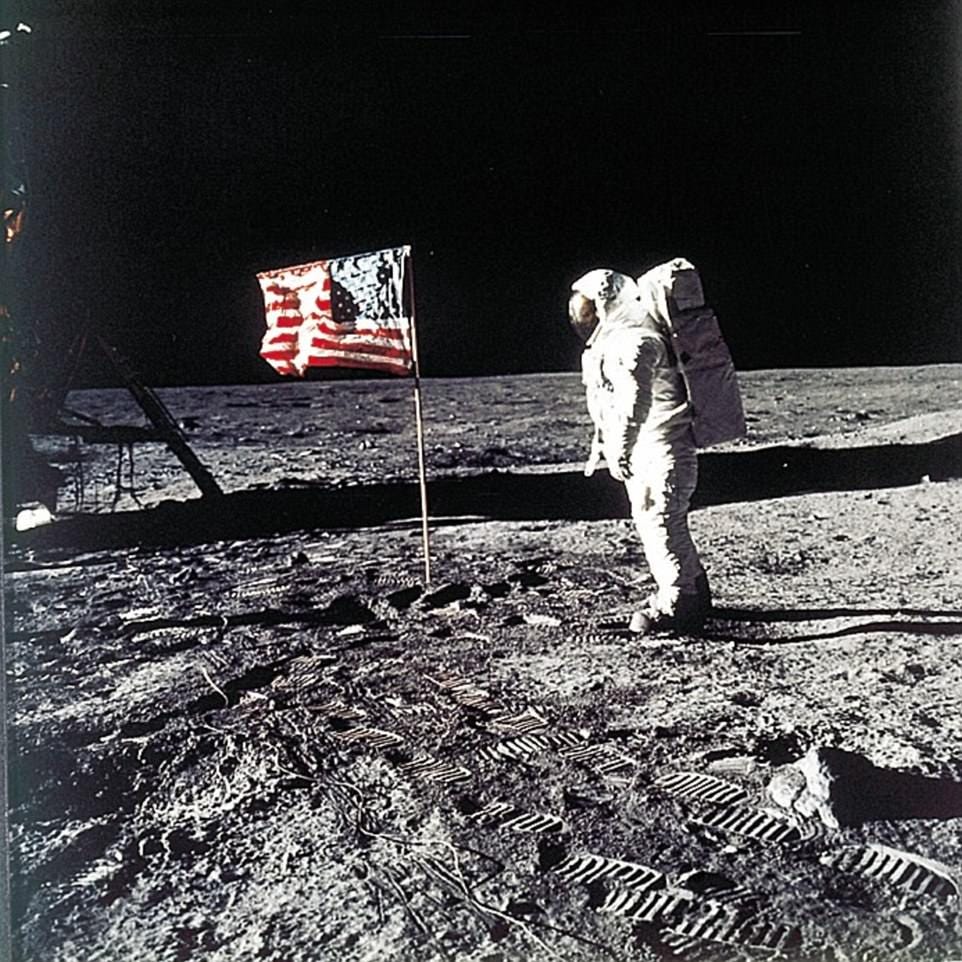

Sometimes this becomes a puzzle for the reader, too, as we try to see past Severian’s interpretation, trying to understand what it is he’s actually describing. A famous example (so subtle I missed in in my reading) is Severian describing a painting:

The picture …showed an armored figure standing in a desolate landscape. It had no weapon, but held a staff bearing a strange, stiff banner. The visor of this figure’s helmet was entirely of gold, without eye slits or ventilation; in its polished surface the deathly desert could be seen in reflection, and nothing more.

Seeing past Severian’s interpretation, we realize this is the famous photo of the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, but so far in the past to him he has no idea what it is.

What in the Heck is a “Hierodule”?

Wolfe’s prose mirrors this tone—dense, archaic, rich with allusion and ambiguity. He frequently uses forgotten and obscure words (often real but derived from Latin, occasionally invented). This is not to be clever, but to reorient our perspective. We readers are the foreigners here, groping for meaning in a foreign world.

The new terms are never explained, just sprinkled casually into the text. For example:

…I heard voices and the sound of many marching feet behind me, I only moved a pace or two into the trees and watched openly while the column passed.

An officer came first, riding a fine, champing blue whose fangs had been left long and set with turquoise to match his bardings and the gilt of the owner’s estoc. The men who followed him on foot were antepilani of the heavy infantry, big shouldered and narrow waisted, with sun-bronzed, expressionless faces. They carried three-pointed korsekes, demilunes, and heavy-bladed voulges. This mixture of armaments, as well as certain discrepancies among their badges and accoutrements, led me to believe that their mora was made up of remains of earlier formations. (p.717)

Mora? Antepilani? Sure, I can guess what korsekes, demilunes, and voulges are (weapons) but I cannot picture them in my mind. And Wolfe does not define or describe them, either.

I imagine this will frustrate many readers. If that’s you, find yourself a glossary of terms for New Sun. But I love not knowing. It adds to the fictional dream: Severian is telling readers (me) something he assumes I know.

This has its greatest effect in one of the most chilling moments in the book: Severian’s encounter with an “alzabo”—a wolf-like creature that consumes the dead and absorbs their personalities, even speaking in their voices. The alzabo calls a mother in the voice of her lost child. It speaks to Severian in the voices of those it’s eaten. The alzabo’s horror lands not just in the grotesque image, but in the vague unknowing of what exactly this alien “thing” is or looks like, and where it comes from.

Memory and Meaning

A quick return to what may be the book’s most daring choice: its narrator. As I mentioned above, the story is told in the first person, past-tense, as Severian recounts the tale of his ascent to greatness. He insists he forgets nothing—that his memory is perfect. And yet we are sometimes left wondering if he is deceiving us. Or himself. What is the truth of this text?

And this Severian is not always likable, either. Yes, he is curious, brave, and intelligent—but also arrogant, unthinking, and occasionally cruel. His treatment of women…well, let’s just say it’s not ethical.

Part of the brilliance of Wolfe’s structure is that we, the readers, are asked to do the work of interpreting what a very real, very flawed person chooses to tell us. We must read not just what our protagonist, Severian, tells us, but also what he doesn’t. We must watch his actions, question his choices, and imagine the gaps in his recollection.

Much as Wolfe drops unfamiliar words, he never holds our hand when it comes to Severian—or anything else for that matter. And that’s part of his greatness. There are no easy answers, and the book respects the reader’s intelligence more than almost anything I’ve read.

Final Thoughts

I know what I’ve written barely scratches the surface. I haven’t even touched on the deep religious symbolism (Wolfe was a devout Catholic), the intertextual echoes of classical myths and literature, the sly humor. There is more going on here than in most ten-book fantasy series, and my goal is simply to give you the lay of the land to see if it’s for you.

All I can say is this: if you are willing to surrender to Wolfe’s world—to let go of your expectations, to embrace the confusion, to read slowly and carefully—you’ll enjoy it.

And you may find yourself transformed. I did.

And I suspect I’ll be reading The Book of the New Sun again before long. Not because I missed something (though I 100% did!), but because some books are not just read, they are lived with.

Thank you for visiting the Reading Room!

In my next post, I want to dig a little into Wolfe’s symbolism, as well as his story structure—how he breaks many of the so-called “rules” of writing a novel, and yet somehow creates something more powerful, more immersive, and more haunting than most writers today could achieve.

The Reading Room is and always will be a free publication. I want to connect with you about books and writing—not make money off you.

Take care!

![Gene Wolfe - The Book of the New Sun [comprising] The Shadow of the ... Gene Wolfe - The Book of the New Sun [comprising] The Shadow of the ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Xogg!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc5dcca8c-de22-4a49-97d2-36769a317c9e_905x398.jpeg)

Good stuff here. Sorry if I sound a bit ranty but I think it is also important for people to know that just because a book is generally treated as a masterpiece it does not mean you have to like it.

For me the Shadow of the Torturer fails because of the following reasons:

- Severian is inconsistent in almost every way and mostly a passive MC. Sometimes he randomly exerts command and tries to dominate others but most of the time he basically just lets things happen to him with barely any reaction

-The characters don't behave like humans. I could not tell you of any character that pops up because of their personality. All characters are dull and feel more like functions for the poem. Yes I said poem because saying this is a story would be a stretch.

-All the interesting world building is in the background and it just comes and goes like an inconsistent magic system. You are left to scrounge up details and see if you can put together how the world works.

With all that said. I know that the things I mentioned above are completely subjective. Some people are looking for narratives like that. However I just wanted to leave this comment so that you know what you are getting yourself into.

Wolfe's writing prowess is impossible to understate. The series ended about the same time McCarthy's Blood Meridian was published. Wolfe every bit as good as McCarthy and certainly more versatile.